Living a better fiction

“I wouldn’t say that being trans now is living my truth. I’d say it’s a better fiction. This is the genre of this body now. This is how it breathes easy. It’s telling that transsexuals are required to declare we’re in possession of true being to transition—a demand not made of other sorts of body. Memoir, the account of true self, is demanded of us. Fuck that.” – McKenzie Wark, Love and Money, Sex and Death

I have been spending a lot of time lately thinking about truth and fiction. As I approach the beginning of my creative nonfiction MFA program later this year, it’s hard to escape pondering these supposed opposites, try to tease out the distinctions, especially as they manifest in the writing work I’m supposedly agreeing to pursue. The word nonfiction suggests something real, immutable, plainly visible; yet this idea of a creative nonfiction, something that toys with the truth, creases its edges, leaves plenty up to the imagination, makes it easy to wonder if truth and fiction are so diametrically opposed after all.

Today is the 50th anniversary of Candy Darling’s death. Last year on this same date, I was just over two weeks out from my first Facial Feminization Surgery, and as I recovered, I decided to watch Beautiful Darling, the documentary film about her life. It was sheer happenstance that I watched the film on the anniversary of her passing, yet the experience was devastating in the best possible way. That day, I wrote her and the artists ANOHNI and Chloe Dzubilo a poem, feeling myself present with these older trans women, two now deceased, who had made themselves into the women they wanted to become, even when the world around them could not see their vision. The poem alludes to Ahnoni song “For Today I Am A Boy,” which appeared on the album I Am A Bird Now, which features Candy’s deathbed photo (taken by Peter Hujar, who I wrote about in a previous newsletter). Candy was the first trans woman I ever saw, a gift that AHONHI gave me 15 years ago, when the idea of becoming a woman was the most far-flung fiction I could imagine. As I wrote in the poem:

I knew so little about Candy;

But it was you who made introductions,

showed me her dying face,

asked me, for the first time in my life,

if I too might like to grow and become

a beautiful girl, as she was, and Chloe,

and you.

Next week I’ll have a review out of Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar, a remarkable new biography of Candy’s life by Cynthia Carr. As one of her friends said of Candy’s process of self-creation in the book, “Candy had a vision of herself and she became that vision.” Even now, these words have an incredible resonance, a much-needed reminder of what we can conjure through sheer force of will. Sometimes, it is not enough to know the truth about ourselves for it to become what we most need for ourselves. Even if the version of ourselves we want to believe in is a fiction, our imagination can still be a guidepost towards the world we need to create to make that possible in a sustained way in our day-to-day lives.

Poet George Stanley is quoted at the beginning of Samuel Delany’s brilliant speculative fiction novel Dhalgren, where he says, “You have confused the true and the real.” In some readings of the quote, there’s a suggestion of delusional thinking, of being so lost in a fantastic image in the mind’s eye that the veracity of everyday life has been torn asunder. As I tried to search for the quote, forgetting its place at the beginning of Delany’s book, Google repeatedly offered me suggestions of dissociative psychosis, this ominous, dreadful feeling of having lost touch entirely with the world as it is currently constituted. It’s a distressing feeling, but one entirely understandable today: with election year dread bubbling up within me, this urge to vacate reality entirely, to plunge headlong into the fictive realm of the imagination, is an alluring proposition.

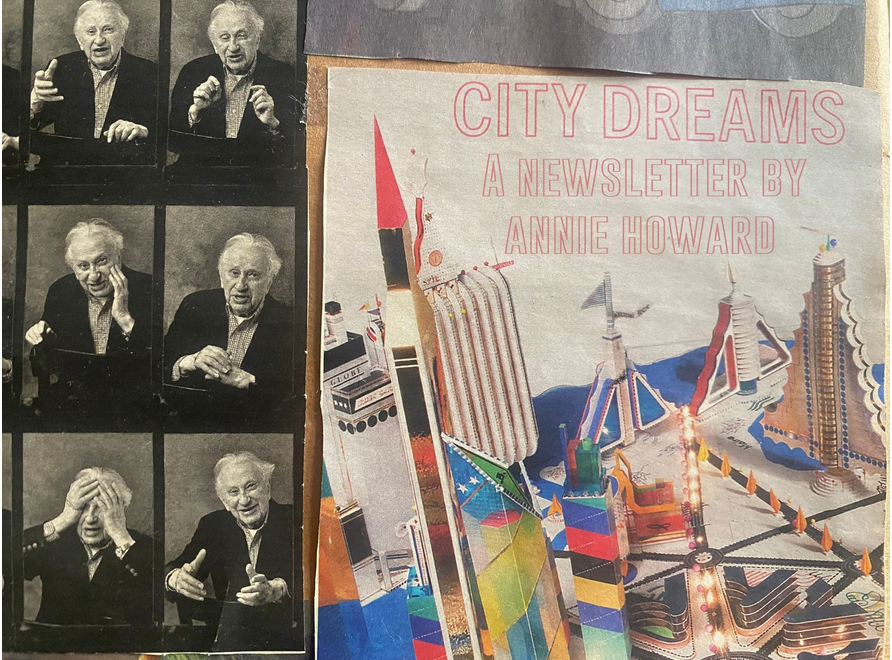

Such an approach is always tempting. Yet as the opening quote to this newsletter from McKenzie Wark suggests, I think it’s okay to grant fiction an operative role in our lives, to inhabit the kind of fantasy that sustains us when a hollow sense of reality is too much to bear. I interviewed McKenzie at Women & Children First last week, and in our conversation, we talked about women like Candy Darling, who blazed a pathway that continues to inspire us today. Even though Carr’s biography suggests Candy often struggled to believe in the fantastic image of herself she’d created, to know that she found herself at all, when so little in the world suggested her life was even possible, is all I need to remember when I lose purchase on day-to-day reality.

In one of her journals, Candy wrote, “I will not cease to be myself for foolish people, for foolish people make harsh judgments on me. You must always be yourself, no matter what the price. It is the highest form of morality.” Every day brings fresh reminders of the foolish people who want trans life banished from this world, and to see their power to warp material reality gain purchase offers grim portents of worse times to come. But if daily survival today often means a retreat into the fantastic imagination of a future where trans life is abundant, unbothered, and celebrated, I know this much to be true: we’re not going anywhere. As I’ve learned from Candy, Chloe, Ahohni, McKenzie, and countless others, our persistence is a testament to something far greater than any of us, this fundamental sense of mutability present in every living being that is made a little more obvious to trans people. Call it truth, call it fiction, I don’t care either way. A sense of stubborn imagination prods me to stay on track, to step daily into unknown experience, certain that this life is always worthwhile, no matter what stories are necessary to persevere.