An echo of the city

I keep hoping that when I do a picture, it has its own life that really has nothing to do with that moment. It’s not something frozen. It’s the echo of that time and that what’s on that piece of paper has its own life. Which is very different than the life that was, in the moment that the picture was taken. – Peter Hujar

Peter Hujar saw things differently. In a time in which New York City was widely assumed by many outside of it to be crumbling, undone (so the story went) by the largesse of the city’s welfare system, Hujar was there to document the life that happened anyways. Aiming his camera at those in the art worlds that populated the city in the 70s and 80s, especially amongst a queer underground that we now look back upon with reverence and awe, Hujar knew how to bring his vision to the most intimate moments with his own tenderness, capturing something that could live well beyond that instant, as his above quote suggests.

I first met Peter’s work through the album cover of Anohni and the Johnson’s 2005 album I Am A Bird Now, in which Anohni used Hujar’s photograph of 29-year-old Candy Darling on her deathbed. I knew so little of the world that Darling and Hujar once occupied when I first heard the record as a teenager, but in a small way, Anohni made introductions to a time and place that’s haunted me for several years now. I wrote a poem about Darling’s death this spring, watching a documentary on her life on the day that she had passed, 49 years before. Sitting in silence during my recovery from Facial Feminization Surgery, and seeking the company of others who I will never meet, was something I was lucky enough to do at length in March, something that remains present with every encounter I get to these lost people and the worlds they inhabited.

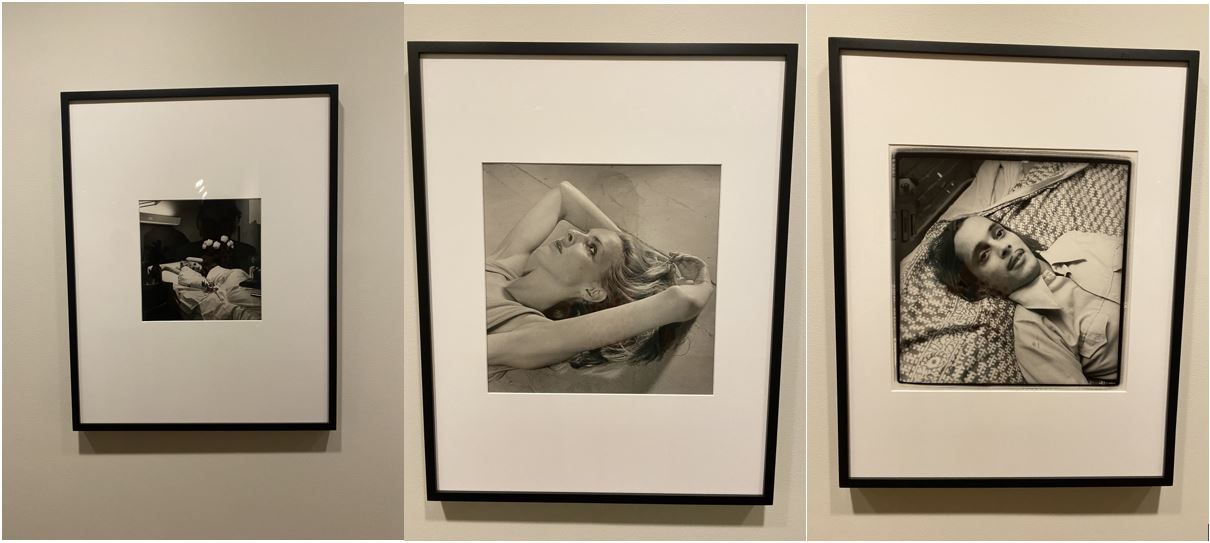

It was, of course, I Am A Bird Now that I put in my headphones upon visiting the Art Institute by myself a few Fridays ago to visit the Candy portrait in person. Before going, I didn’t realize the piece was there as part of a larger Hujar exhibition; within minutes, I found myself sobbing throughout the gallery, seeing so many familiar faces captured in such intimate moments. Portraits of John Waters, Gary Indiana, David Wojnarowicz, Greer Lankton, and more greeted me, alongside new names and faces I’d yet to meet: images of Larry Ree, Ethyl Eichelberger, and the Palm Casino Revue suggested new avenues for exploration, unknown maps of outmoded examples of queer urban life that I’d yet to encounter.

Yet whether the face I watched was one I’d seen before, or made introductions to someone new, something fundamental remained the same: Hujar’s ability to capture his subjects at their most open made me feel like I’d stumbled into other people’s intimacies, offering a level of vulnerability that we’re lucky enough to share in our own lives with a finite number of others. I have, at times, found myself hopeless to a sense of reverie for the ways in which others have called cities like New York or Chicago home, been told with love and care that my yearnings for the past were blinding me to my very own time and place, my ability to see those around me with as much reverence as I’ve treated the past. It’s a delicate dance, one I have admittedly failed at times. Still, I could not deny that each portrait offered an “echo of that time,” that these images could live with me in the present moment, able to offer a specific kind of catharsis in the now, just as Hujar would have wanted.

I could also not help but think about The Power Broker, Robert Caro’s massive biography of Robert Moses, the man whose overwhelming influence on the development of New York in the 20th century remade the city to his own specifications. Witnessing Hujar’s images of the decaying piers where gay men would once cruise one another, or photographs of Wojnarowicz in an abandoned apartment building, a ghostly figure splayed out on a broken box spring, I couldn’t help but feel anger in the knowledge that the city had been so decimated by Moses’s policies, had torn up working-class neighborhoods to build expressways while beating communities into a jagged, unsalvageable mess. I’ve been reading the book for the past month, and around when I saw the Hujar show, I reached a chapter, “The Point of No Return,” in which Moses’s unyielding commitment to highway development left the city unable to build the transit infrastructure necessary to prepare itself for the decades and centuries to come.

Whatever beauty there was in Hujar’s images, and the ways in which they revealed a queer underground that made use of a city that had been treated with such disregard by Moses and other policymakers, I was forced to think about our own decaying moment, to think about my friends in New York and the flash flooding that struck the city last week. Witnessing a city once more on the edge of collapse, I thought of the great beauty that remained possible within that chaos. Still, with each passing day it’s hard not to feel that the damage has already been done, that the best we will ever do is to make do in the ruins of other people’s bad decisions. Thankfully, Hujar and his friends gave us models for such calamitous times; it’s in large part this sense of creation on the edge of the abyss that makes me so grateful to return to these works in our own time. Whether we will be able to pass along our own creations to some future generation, wondering how they might survive amidst great tragedy, is a question best left unanswered.